Double Stop Position Playing

The double stops that form intervals of fourth, a major third, and a minor third form an important framework that informs how I see the mandolin fretboard and how to navigate between different positions and through chord changes.

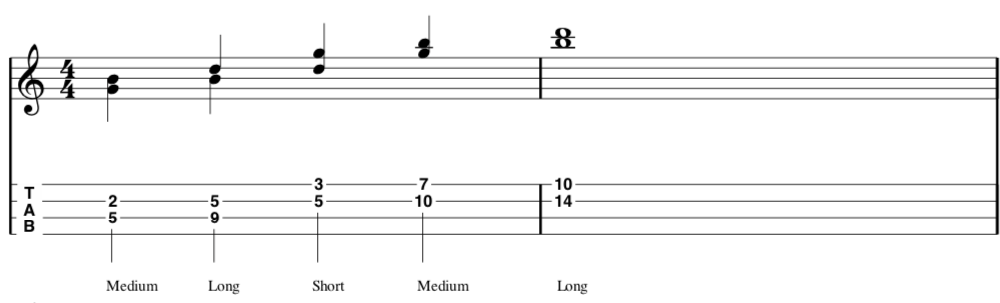

Sharon Gilchrist, I think, was the first person I heard call these the short, medium and long double stops and I like that way of describing them. Before hearing that I always called them by the intervals that they form, the perfect fourth, the major third, and the minor third.

The short double stop is the one that has a difference between the lower and higher strings of two frets (or one empty fret between your two fingers). That interval is a perfect fourth, which is also an inversion of a perfect fifth and, when I am thinking around the fretboard, it is mostly that fifth to root relationship that I am considering when using this double stop.

The medium double stop has a difference of three frets between the the lower and higher strings and the interval is a major third. A major third is the interval between the root and third in a major chord, and it is also the interval between the third and the fifth in a minor chord.

The long double stop is the one with a four fret difference between the lower and higher strings. This interval is a minor third. Minor thirds are sometimes played as the interval between the root and minor third of a minor chord, but they are also the interval between the third and fifth in a major chord, and the interval between the fifth and seventh in either a seventh chord or a minor seventh chord.

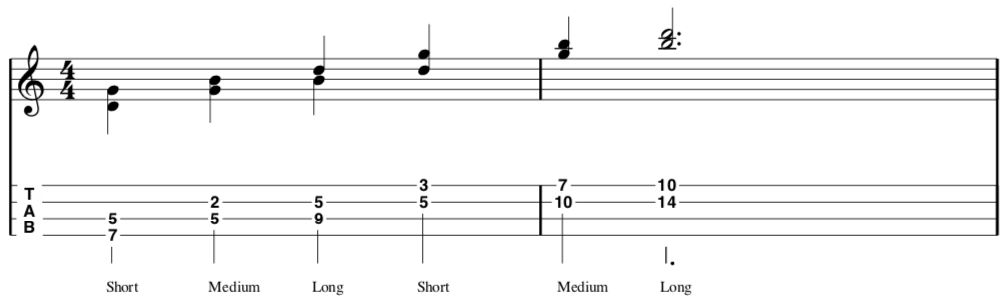

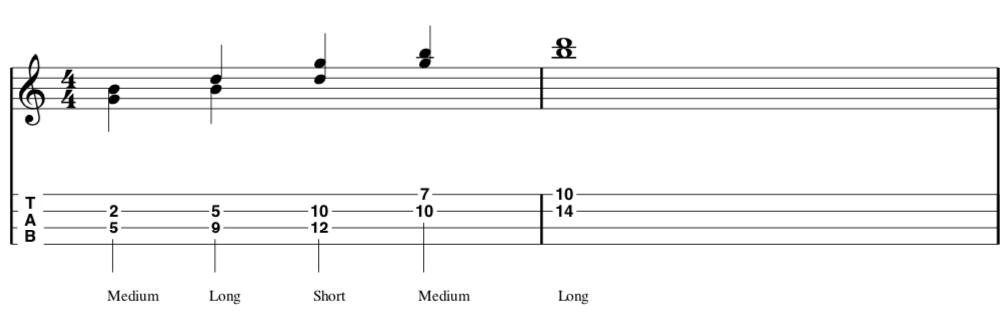

The following example shows some double stops that demonstrate the short, medium and long positions and are part of a G chord

So, how does this all come together to help us navigate the fretboard? I look at these double stop positions not only as small chords, but as part of the system I use for navigating the fretboard in any key. The finger positions of these double stops create home positions that my hands fall into. Learning to see how different chord and scale pattern overlay these positions brings a great sense of order to the fretboard.

One insight from understanding these double stop positions is in reinforcing our knowledge of arpeggios as it gives us some redundant information that I think helps us naturally move around while playing over one chord.

Starting with any one of the double stop positions, there is a major arpeggio pattern that uses all three double stop positions as string crossings. Each of these places at most two notes on each string. The same is true for minor arpeggios.

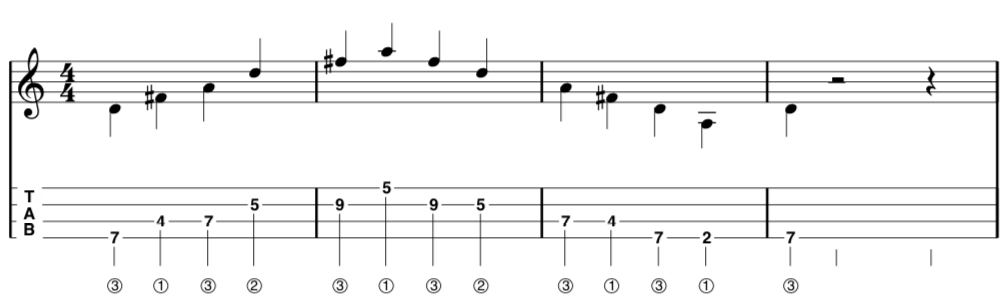

Here is a first example with a D arpeggio that begins on the 7th fret, and the string crossings use the double stop positions M, S, L in order.

Here is an example of a G arpeggio that begins on the 7th fret, and the string crossings use the double stop positions S, L, M in order.

The cyclical pattern of the double stop positions in these string crossings is small, large, medium, small, etc. In the example above, our first crossing was a small double stop, from the fifth to the root.

As a third example, we have a closed A arpeggio pattern that has the first string crossing using the minor third interval between the third and the fifth, which is the long double stop fingering. Here, as you would guess from the above information, the ordering of the positions used at the string crossings is long, medium, short.

That gives us three cornerstone finger position patterns to learn that I think of as similar to the CAGED system that guitar players learn. Most of the time I’m playing, my hands are hovering over one of these positions. I will cover where to find various passing notes from these positions later, but meanwhile, noodle around think about how you might find and use passing notes like the sixth, flat seven, flat third, fourth etc. from each of these arpeggio positions.

On any pair of strings, taking any of the three double stop positions as two notes in a major chord, the next double stop that is part of the same chord is on that string pair in a pattern that follows, small, medium, large, small (until you run out of frets).

The cyclical pattern of these up the neck double stop positions is small, medium, large. This is because in each of these moves, the higher note becomes the lower note of the next double stop – fifth to root (short), root to third (medium), third to fifth (long), fifth to root, etc. These can occur on a pair of strings of by a (down neck) shift to an adjacent pair for a series going up in pitch.

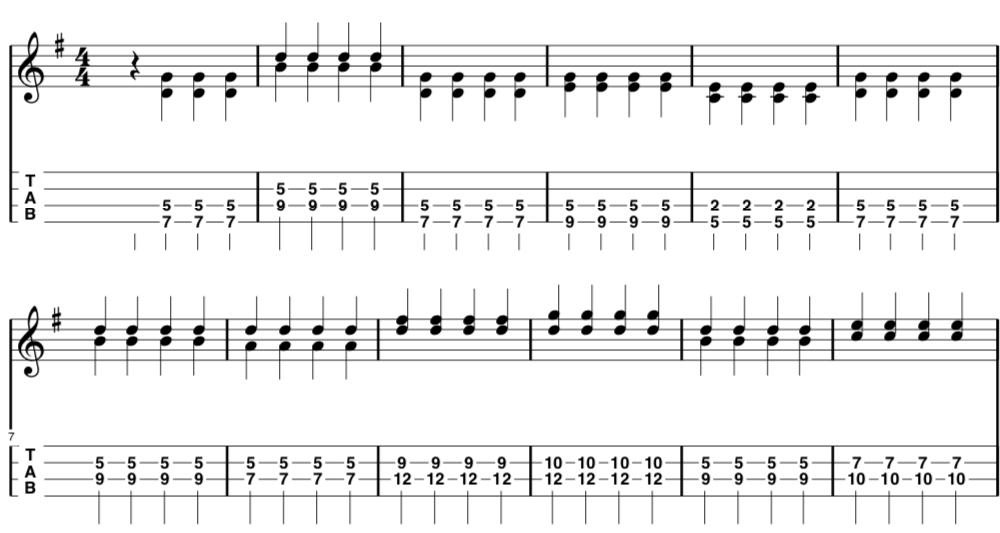

Here’s a few examples in G, expanding on what we saw in the first example:

Or alternately, if a down-neck shift is needed

Another important observation about these double stops is the patterns for chord changes over 1 4 5 chord progressions.

Starting with any of the short, medium, or long double stop as a part of the I-chord, a double stop that is part of the IV-chord and one for the V-chord can be found nearby using the other two double stop positions.

This gives us a way to find, from one double stop position, the nearby position for intervals that are part of the next chord in the song.

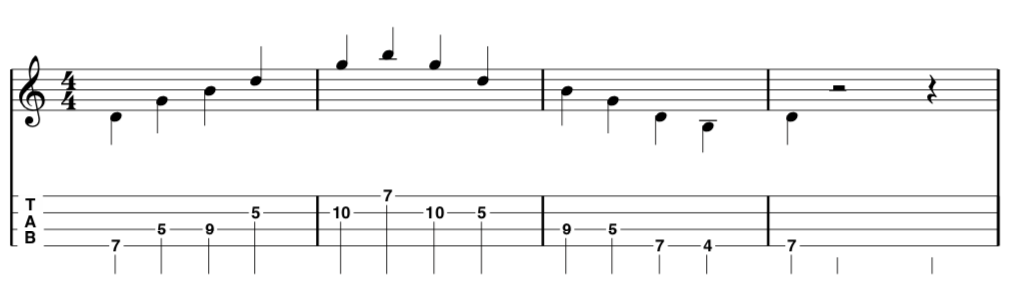

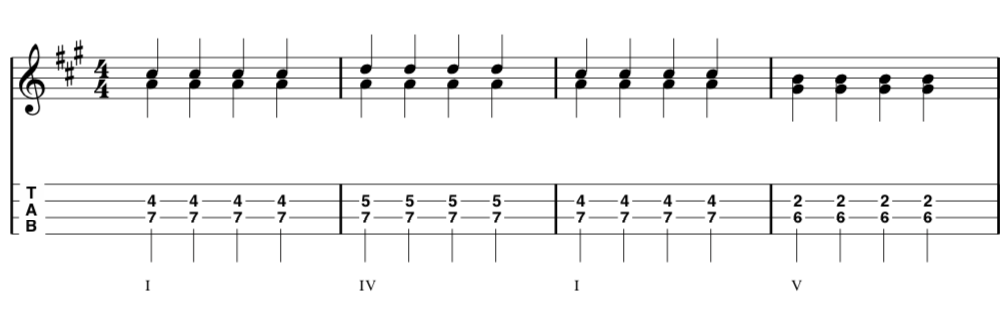

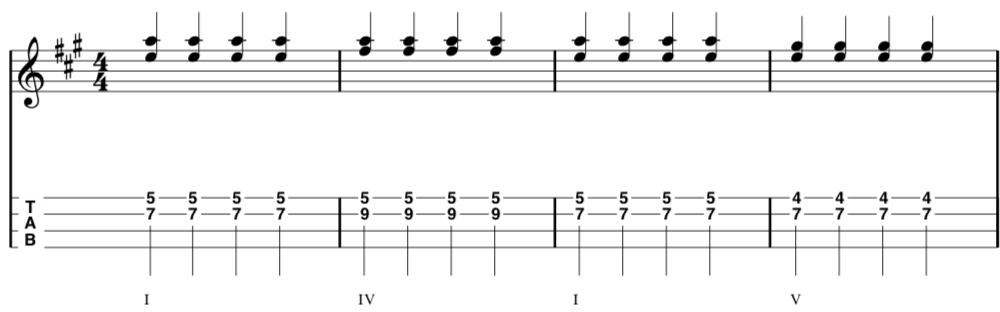

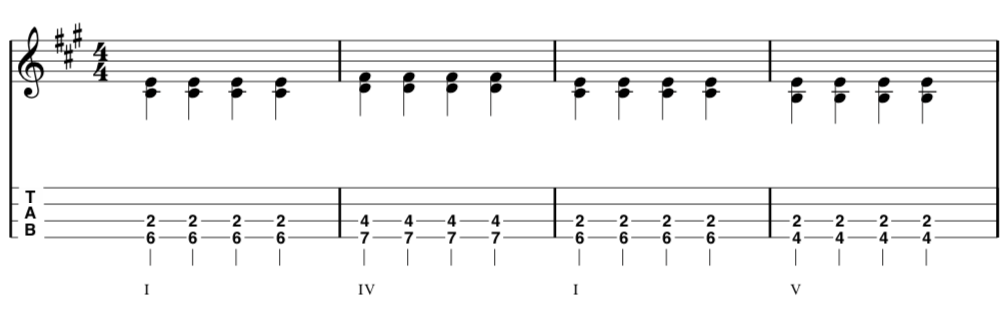

The following three examples are in the key of A. Each is based on the same progression I-IV-I-V.

The first example begins from a medium double stop and uses a short for the IV chord and a long for the V chord

The second example begins with a short double stop for the I chord. It uses a long double stop for the IV chord and a medium double stop for the V chord

Finally, we have an example in which the I chord is being played as a long double stop. The IV chord is played by a medium double stop and the V chord uses a short double stop.

Taken together, by mastering just these three patterns in italics above, it becomes much easier to move across the strings as well up and down the neck. And since this is based on closed positions, no open strings, playing in any key becomes a lot more manageable.

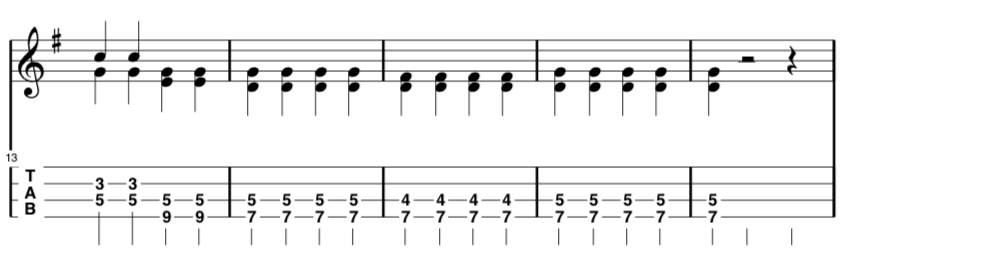

Let’s look at an example using a familiar chord progression, such as in Your Love Is Like a Flower. This might be a typical movement between positions that could be utilized in a solo in that song. Later, when we look at passing notes and other notes from these positions, we can fill in a more interesting solo, but for now just focus on how we shift around as we move through the chord changes.

In a further post we will look further at passing notes and how to build licks around these positions . (I think I’ll also make separate posts that go into a little of the interval theory that I sort of assume above.)